It is difficult for me to ascertain when the person I am communicating is using a logical fallacy to trick me into believing him or doubting my judgement, even when I realise it hours after the argument.

I have seen countless arguments in Reddit threads and I couldn’t figure out who was in the right or wrong unless I looked at the upvote counts. Even if the person is uttering a blatant lie, they somehow make it sound in a way that is completely believable to me. If it weren’t for those people that could exactly point out the irrationality behind these arguments, my mind would have been lobotomised long ago.

I do want to learn these critical thinking skills but I don’t know where to begin from. I could have all these tips and strategies memorised in theory, but they would be essentially useless if I am not able to think properly or remember them at the heat of the moment.

There could be many situations I could be unprepared for, like when the other person brings up a fact or statistic to support their claim and I have no way to verify it at the moment, or when someone I know personally to be wise or well-informed bring up about such fallacies, perhaps about a topic they are not well-versed with or misinformed of by some other unreliable source, and I don’t know whether to believe them or myself.

Could someone help me in this? I find this skill of distinguishing fallacies from facts to be an extremely important thing to have in this age of misinformation and would really wish to learn it well if possible. Maybe I could take inspiration from how you came about learning these critical thinking skills by your own.

Edit: I do not blindly trust the upvote count in a comment thread to determine who is right or wrong. It just helps me inform that the original opinion is not inherently acceptable by everyone. It is up to me decide who is actually correct or not, which I can do at my leisure unlike in a live conversation with someone where I don’t get the time to think rationally about what the other person is saying.

Note that a fallacy is a reasoning flaw; sometimes the goal might be to trick you, indeed. But sometimes it’s just a brainfart… or you might be dealing with something worse, like sheer irrationality. That said:

- look for the conclusion. What is the point that the writer is delivering? (Note: you might find multiple conclusions. That’s OK.)

- look at what’s being used to support that conclusion. What is the core argument?

- look for the arguments used to feed premises into the core argument. Which are they?

Then try to formalise the arguments that you found into “premise 1, premise 2, conclusion” in your head or in a text editor. Are the premises solid? Do you actually agree with them? And do they actually lead into the conclusion? If something smells fishy, you probably got a fallacy.

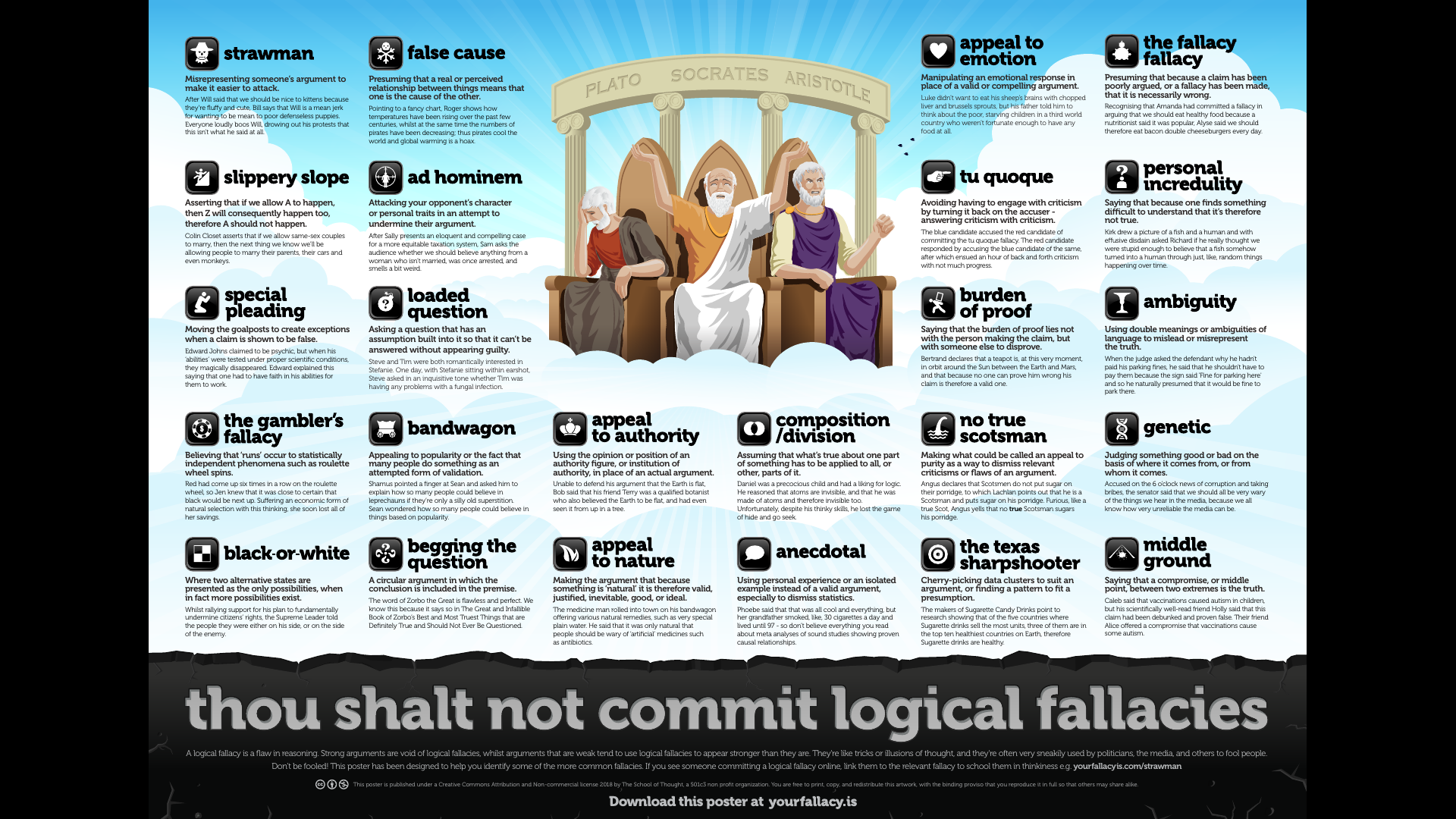

Get used to at least a few “big” types of fallacies. There are lists across the internet, do read a few of them; you don’t need to memorise names, just to understand what is wrong with that fallacious reasoning. This pic has a few of them, I think that it’s good reference material, specially at the start:

In special I’ve noticed that a few types of fallacy are really common on the internet:

- genetic fallacy - claiming that an argument is true or false because of its origin. Includes ad hominem, appeal to nature, appeal to authority, ad populum, etc.

- red herring - bringing irrelevant shit up as if it supported the conclusion, when it doesn’t matter. In special, I see appeal to emotion (claiming that something is false/true because it makes you feel really bad/good) all the time.

- oversimplification - disregarding key details that either stain the premises or show that they don’t necessarily lead to conclusion. False dichotomy (“if X is true, Y is false” in situations where both can be true or false) is a specially common type of oversimplification.

- strawman - distortion of an opposing argument into a way that is easier to beat. Again, notice that “intention” doesn’t matter; only that the opposing argument isn’t being addressed.

- moving goalposts - when you counter an argument, the person plops another in its place, without acknowledging that it’s a new argument. Often relies heavily on ad hoc (making stuff up on the spot to shield an argument)

- four terms - exploiting multiple meanings associated with the same word to create an argument like “A is B¹, B² is C, thus A is C”.

There are also some “markers” that smell fallacy for me from a distance. You should not trust them (as they might be present where there’s no fallacy, or they might be absent even when the associated fallacy pops up); however, if you find those you should look for the associated fallacy:

- “As a” at the start of a text - genetic fallacy, specially appeal to authority

- “Trust me” - red herring, specially appeal to emotion (once you contradict the argument there’s a good chance that the other will create drama because you didn’t blindly trust them, so the whole thing boils down to “accept this as true otherwise you’ll hear my meltdown”).

- “I don’t understand” followed by a counter-argument - strawman. Specially common in Reddit.

- “Actually” - red herring through trivia that is completely irrelevant in the context.

- PatFusty ( @PatFussy@lemm.ee ) 9•1 year ago

Sometimes a strawman gets more upvotes/reception than a well thought out argument. Its difficult to win over people when their minds are made up in the first sentence. It only gets harder if you are doing this irl so your best bet is to gaslight them before they gaslight you. Its the American way.

Generally a good approach is to try learning the rules of logic. Logic is all about proving things to be true using only facts. It can also be helpful to try some logic puzzles or riddles which can only be solved using hard logic. Note that this won’t automatically make you a better critical thinker, but it will help you exercise that muscle.

Also, it’s helpful to play devil’s advocate. If you hear someone making an argument, try to imagine how you would dispute that argument if you disagreed with it. It doesn’t matter if you actually agree or not, just imagine you did and think about what your counter argument would be. This is what high school debate teams have to do; they are given a topic and a position and have to defend their position.

It always helps to be aware of the facts, or at least of how to find facts. If you see a debate happening where you can’t tell who is right, do your own research on a site like Wikipedia and try to see what the truth is for yourself. Not every argument has a correct answer, but you will at least be able to see where each side is coming from.

So I’m not sure how applicable this is - I’m a programmer, and I’m not neurotypical - but here’s how it works for me

If this, then that. When a certain trigger happens, I’ve conditioned myself to stop my train of thought and reevaluate

When I realize I’m uncomfortable or agitated, I first ask myself “am I dehydrated? Am I overheated?”. If not, I look at the situation… If I’m talking to someone and feel agitated, is it because of something that happened earlier today, is it because I’m just in a mood, or is there any other reason this is a me thing, and snapping at them would be unfair.

It’s a lot of introspection, and I’m not sure it applies to someone who doesn’t need coping mechanisms like this… But here’s how it applies to logical fallacies:

If someone says something I feel is wrong, first I ask myself, why do I think that?

Maybe I’ve been taught wrong. I first heard the vaccines cause autism from a parent who said “I think he was susceptible, and the shock to his system from the vaccines triggered his autism”. On it’s face, that made sense - it wasn’t until a coworker sighed and walked away after a comment I made that I googled it, and there was evidence against it and none for it, so I changed my mind immediately. I had no facts, one opinion by someone with a personal stake in it, and so I was wrong.

So if I only “know” a thing because I was told or because I assumed it, I immediately pull out my phone and look for evidence. You can do it very quick with practice, and people generally respond well when you take them seriously - either you go “huh, I guess you’re right” and they’re all smiles, or you show them what you found and go into the conversation with sources - either they can refute the source or you know they’re ignoring the numbers

So now, let’s say you’re arguing something not so clear-cut, I have a reason to believe what I do based on facts, but the answer isn’t obvious.

So first off, I don’t care if you’re the surgeon general or an anonymous Lemmy poster - ideas matter, people don’t. The only time you trust authority is when you aren’t able to understand the issue - and that comes up plenty, but it has no place in a conversation about the issue - you should be trying to understand ideas if you’re talking about it. If they bring up a person, that’s not an actual argument… Just ignore the names and the titles.

Hitler was right about some things, George Washington was wrong about some things - pretending otherwise is dumb. I’m on Hitler’s side about interior design… Nazi stuff looks imposing and regal. I’m also Jewish, so I’m not exactly a fan of the guy. Ideas matter, where they come from has nothing to do with anything

Next, is “if I can’t understand why someone would do/think this, I’m missing facts”. If you can’t give me a solid argument for the other side, I take everything you say about the topic with a grain of salt. No one is evil in their own story, no one takes a hilariously bad stance just because they’re dumb… They have a reason to think that way, and if I can’t understand why, then I’m missing something.

And if I’m missing something, it’s foolish to make up my mind before I hear what that is.

Then you get to the actual arguments. I lay it out in my head. I break down the individual statements - do they make sense individually? Are they actually related to each other?

Most of all, it’s important to see the difference between winning the argument and making a point. I’m not a great speaker - i don’t remember specifics well, I remember my conclusions. I lose arguments all the time, and I pride myself on the fact that if I realize I’m wrong, I’ll turn on a dime and own up to it.

But winning an argument and being right are almost unrelated things.

Finally, go back and fact check. The argument might be long over, but the goal should always be to understand better and gain a deeper perspective - follow up for your own sake

So my advice is: stop, reevaluate, and refocus. Every time something doesn’t sound right to you, take a minute. Take a breath, remember your goal, and decide if what you’ve just been told changes that.

It’s easy to get buried in details or lost in the heat of the moment, so make a habit of taking yourself out of it

Logical fallacies don’t necessarily disagree with facts. While the most common examples are simply unsupported statements that sound supported, very often we don’t have the luxury of working with clearly factual statements as a basis.

All rhetoric is at the end of the day a fallacy, as the truth of the matter is independent on how it is argued. Yet we don’t consider all rhetoric invalid, because we can’t just chain factual statements in real debates. Leaps of logic are universally accepted, common knowledge is shared without any proof, and reasonable assumptions made left and right.

In fact one persons valid rhetoric is another persons fallacy. If the common knowledge was infact not shared, or an assumption not accepted, the leap in logic is a fallacy.

I would try to focus less on lists of fallacies or cognitive biases and more on natural logic. Learn how to make idealised proofs, and through that learn to identify what is constantly assumed in everyday discussions. The fallacies itself don’t matter, what matters is spotting leaps in logic and why it feels like a leap in logic to you.

After all, very often authoritive figures do tell the truth, and both sides of the debate agree on general values without stating them. If someone starts questioning NASA or declares they actually want more people to live in poverty, they did infact spot very real logical fallacies in the debate, but at the same time those fallacies only exist from their point of view, and others might not care to argue without such unstated common ground.

Reddit’s obsession with logical fallacies is one of the things I was hoping we could get rid of moving here

Agreed. OP should be working on critical thinking skills in general and not specifically focusing on logical fallacies.

Logical fallacies and argumentation theory in general certainly have their place. But unless you’re taking part in a debate club or otherwise getting really really deep into these topics, they may do you more harm than good in thinking critically and having productive discussions.

The reddit (and, previously, slashdot) obsession with logical fallacies has been almost entirely as a way to prevent critical thinking and end discussion rather than promoting either.

The old Slashdot obsession of calling out logical fallacies lead to the hyper normalisation of climate change denial. We had a whole load of really smart people who were very quick to call out any appeal to authority (of, you know, actual climate scientists), but a bit too lazy to read the source material themselves.

Fun times.

Rather than not encouraging focusing and learning fallacies, maybe we are simply saying that they need to also learn to use them appropriately? Fallacies are not just the informal ones that everyone is referencing here in this thread, but also the formal ones which are very much required for logical argument structure. So even in learning about fallacies, there will be opportunities to understand the difference between informal and formal, why they are different, and how that applies to discourse. Knowledge is power; it just needs to be balanced with understanding on how to use and I think a deep dive into fallacies could actually assist in that regard.

I dunno. For someone just starting to want to think critically during discussions of when reading things, asking them to get serious in the academic pursuit of logic and argument theory might not be the way. For one, it’s probably just asking for them to get stalled in the sort of dunning kruger zone of identifying fallacies and stopping there.

Especially when such behavior is already endemic to the internet and many platforms have feedback loops designed to reward this behavior. Just dunk on 'em and move on - watch the upvotes and retweets roll in.

I definitely don’t want discourage OP from learning anything, but I do want to be careful in what direction we point a beginner.

I think maybe learning to find good sources of information and verify claims might be a better first step. That doesn’t give OP any shortcuts I’m discussions, which is good. Then they may begin to notice different patterns or forms of discussion and at that point they can start to classify them and learn about them if they see fit.

Such good points; I’m convinced. To continue on your line of thinking, after learning some media literacy and starting to notice different patterns and forms of discussion, I wonder if learning Aristotelian syllogisms would be a good next step. So we still aren’t jumping right into fallacies per se, but we start to understand logic structure and what is formally valid/invalid. So now it’s got them thinking about how to structure and challenge their own beliefs and arguments. And while we are now potentially hitting formal fallacies, I think this would not give any immediate tools for dunking on anyone either because, in my experience, converting a real-time argument to a syllogism is very very difficult without a ton of experience and practice breaking arguments down into simpler ideas. What do you think?

Yeah, I like that. After being able to recognize and validate claims, being able to verify the validity (at least logically if not factually) of any conclusions drawn from those claims seems like a good next step.

Should we go ahead and put a curriculum together and start shipping it to universities, or…?

“Truth” is a matter of conclusions and meaning, not of facts. Factual information would be something like–and this is an intentionally racist argument–53% of the murder arrests in the US come from a racial group that makes up 14% of the population. This is a fact, and it can be clearly seen in FBI statistics. But your conclusions from that fact–what that fact means–that’s the point of rhetoric and logic. Faulty logic would make multiple leaps and say, well, obvs. this means that black people are more prone to commit murder. A more logically sound approach would look at things like whether there where different patterns in law enforcement based on racial groups, what factors were leading to murder rates in racial groups and whether those factors were present across all demographics, and so on.

In my sophomore year at college I needed to add a “filler” class to have something to do in campus between my two “real” classes. I chose to take Logic and it was one of the best decisions I ever made. Not only was it interesting, it helped me think and analyze arguments. I am pretty sure there are universities that give you free access to the course but it wouldn’t surprise me if you can find logic courses for free on YouTube as well.

Same here. I write software for a living, but my philosophy logic course was gave me a huge lead as the ability to deconstructe what people say into logic blocks is the first step of writing code.

What helped me: “Rationality Rules” on youtube had a video series (and even a tabletop game) about types of logical fallacies with the focus on religious apologetics.

And as you said: Upvotecount show whose opinion/argument is popular with the viewership. There can be a correlation with how sound the argument is logically.

I’m genuinely curious here, why is learning to identify logical fallacy at the point of conversation that important to you? Just research yourself afterwards, otherwise how would you know what is wrong unless you have already decided or learnt it is wrong to begin with. In my opinion, it is not that important unless you are engaged in professional persuasion or your opinion at the very moment holds a lot of weight. You could maybe identify inconsistency or twist their words until they contradict themselves? Otherwise, the best approach if you are not sure is to find out later. At the end of the day what matters to me most is my opinion, I do not care if I disagree with the person I am interacting with, or if the person disagrees with me. Maybe cause I’m not a politician. ;-)

That seems like a dangerous approach to not care if you disagree with people. Shouldn’t you know if your disagreement with them is based on sound reasoning?

Oh, what I meant is that I wouldn’t care to argue for long if I disagree with the person I am interacting with. I did not mean being stubborn and sticking with the same opinion. I just take into consideration what the person has said, and think or research about it afterwards. Apologies for my unnatural English.

Oops, I have no idea why the comment is reposted many times. I shall try to delete.

There’s this app called cranky uncle and it goes through things like this and then helps to you learn how to identify them. It was developed by a university researchers in Australia with the aim of improving people’s ability to recognise misinformation

Posts like this have me longing for a Save feature…

There is a save feature.

Not yet on kbin.social which is where that user is participating from.

Though there’s always the good old bookmark.

Just bookmark in your browser.

You just have to read them like flash cards. Careful not to get caught in the fallacy fallacy though. A fallacious argument doesn’t mean someone is wrong, it just means they suck at arguing.

Logical fallacies and calling them out are just a tool in the tool box. They’re really only useful though when someone is being maliciously fallicious or their entire evidence base hangs on a fallacy. But even then, they may still be correct.

A good example is “the standard model is true because the pope said so.” This is an appeal to authority fallacy, but the stance that “the standard model is true” is correct anyway.

It doesn’t look like it has been mentioned here yet: https://www.amazon.com/Skeptics-Guide-Universe-Really-Increasingly/dp/1538760533

This book goes really deep into every different kind of logical fallacy.

Mostly Informal fallacies, but I liked that book too!

The Demon Haunted World by Carl Sagan. Any other advice I might have given has already been said. There’s also the audio book version read by Sagan.

I’m a bit new to self-studying logic (and rhetoric) but I think you should learn about “Formal fallacies” and “Informal fallacies”. Formal fallacies are those that arguments that are systematically false, like all A is B, some C is A, some C is not B, therefore all C is A. But in real arguments you have to convert those organic arguments into these terms (which could be the hardest part), and then you find out if it is a fallacy… I remember there was a way to find out if arguments are valid based on adding stars, I’ll probably send it later… But be warned, an argument can be “valid”, but still have the wrong premises! You can say, All cats are on fire, therefore some things on fire are cats… and the argument would still be valid, but rest on false premises… Informal fallacies, I think, are somewhat out of the scope of formal logic, but they are still considered faulty arguments, like Strawman…

I would suggest getting a book called Thinking Fast and Slow, and reading it slowly and deliberately, less than 5-10 pages a day. It not only tells you how to find these kind of fallacies but also why you’re likely to fall for them and how.