Hey everyone! This is quite literally my exact area of expertise - I’m an environmental geologist and I work for a regulatory agency specifically tasked with regulating Leaking Underground Storage Tanks (LUSTs, more commonly just USTs). This article is very doom and gloom, but I wanted to share some information that will hopefully make everyone sleep a little easier.

Tl;DR: Petroleum related cleanup from LUSTs is actually in a pretty good place due to things like state clean up funding and grants, brownfield redevelopment, and mandatory tank replacement and upgrades. Additionally, your two big bad guys in gasoline (Benzene and Methyl Butyl Tertiary Ether, or MTBE, both of which are known carcinogens) do naturally break down over time, and benzene in particular breaks down as it’s exposed to oxygen. There are tons of environmental contamination issues we need to worry about and address, but (for once) this particular area of cleanup is in a pretty good place!

This is not apples to apples because I am licensed and work in a different state than Washington, but many/most of the mechanisms should be the same because all of our programs are managed by the EPA and funding exists for all states in some capacity. First I wanted to address this:

polluters have shifted tens of millions of dollars in remediation costs onto taxpayers

This is both true and untrue. The “shifting” is actually in the form of a gas tax which funds a state’s Clean Up Fund (CUF), which is specifically for the cleanup of UST releases. So every time anyone purchases gas, they are paying into this. At the time these regulations were implemented, every person that owned a vehicle would be paying into this. While it’s not necessarily equitable for a variety of reasons, it’s a commodity that every taxpayer uses (much like the roads we drive on) and the logic was applied similarly. This also helps with another point

Of the roughly 450,000 brownfields in the country, nearly half are contaminated by petroleum, much of it coming from old gas stations

This is also true, but that CUFs also help with this, and brownfield redevelopment is a major priority for the LUST program at the EPA. Most funding programs have an “orphaned” site grant, which provides funding for cleaning up contaminated sites (many of which are brownfields) when a new owner buys the property and it’s been impacted/contaminated by tanks they didn’t own and didn’t contribute to. In my state, Orphaned sites make up about 1/3 of all or our CUF claims. Additionally, EPA has separate grants specifically for brownfield cleanup and additional grants for brownfields in disadvantaged communities (where a disproportionate of brownfields are located). They’re fairly generous with the approval conditions (Even under the previous administration, shockingly), so if you know anyone looking to redevelop an impacted site, have them contact their regional EPA office’s UST section!

Gas stations often bear the names of major oil companies such as ExxonMobil, Shell, and Chevron, but that doesn’t mean those companies actually own the stations.

This is true, and makes sense if you step back and think about it - Pepsi and Coke don’t own very many stores, yet stores globally sell their product. Gas stations are typically owned/operated as franchises, and the owners buy the property, tanks, dispensers, and are the ones that are responsible for maintaining the properties. The franchises are STILL usually large companies though, and ones you recognize - Circle K, 7-eleven, United Oil to name a few. Believe it or not, we prefer when the tanks are from a major company because they never fight us on clean up. It’s cheaper to comply, so they gave up fighting decades ago. Most of my UST cases are still tied to either big 5 oil company, or a not as big but still pretty big franchiser. The third largest culprits are actually local government - specifically fire stations and bus yards. Mom and Pop franchises are the least common, but are usually the most difficult to get cleaned up to to lack of financial resources. They’re also the ones we work hardest with to find funding for.

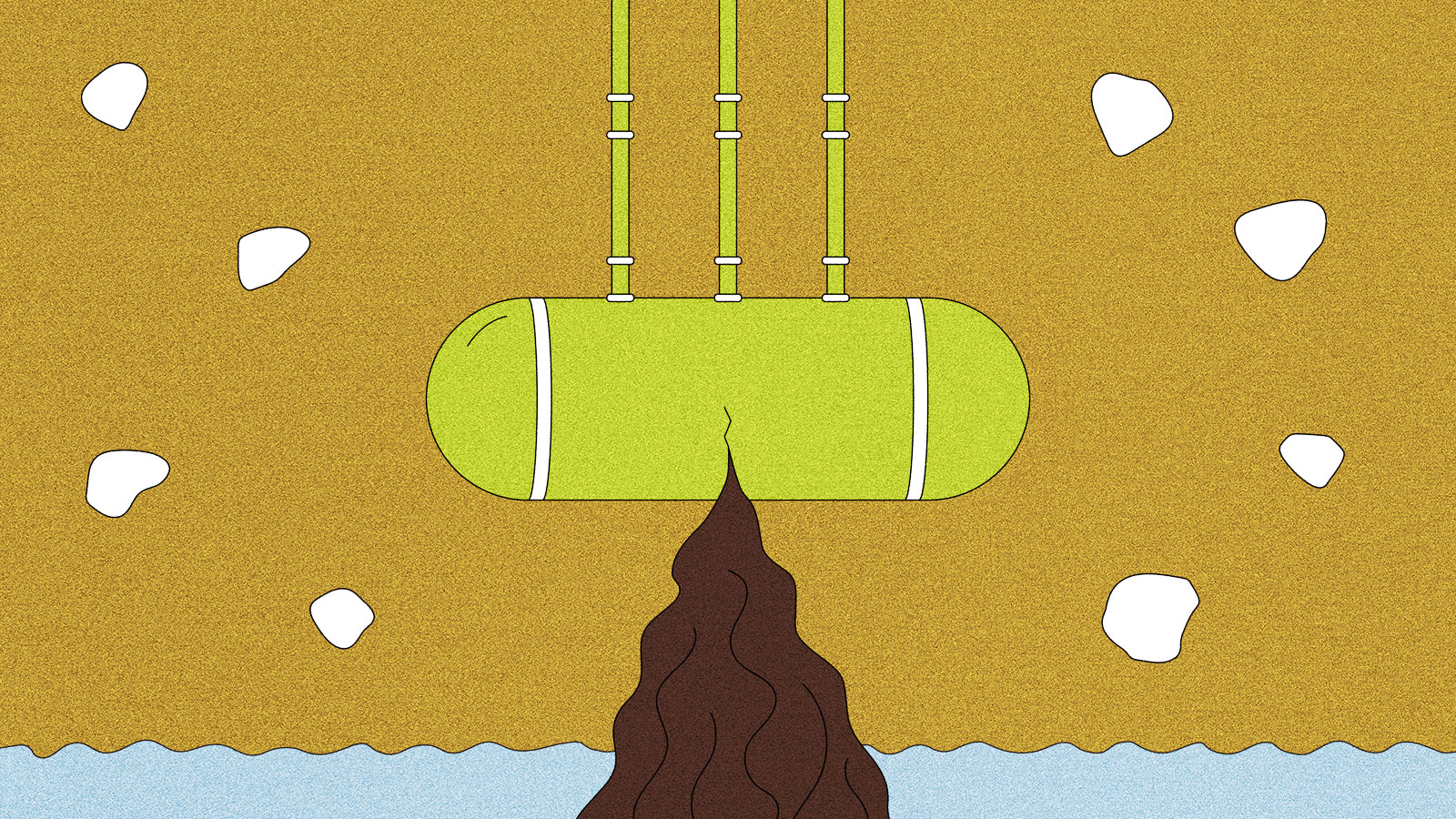

Regarding the tanks themselves - the largest culprit of petroleum is definitely USTs, however, it is specifically single-walled USTs, which were most commonly used from the 50s to the late 80s. Like most environmental issues from that era, it boils down to a) they didn’t care back then, and b) nobody (meaning us small people) knew any better. Most environmental regulation did not come into effect until the 70s, and it’s been a game of catch up ever since. Single walled tanks in all states had a mandatory removal/abandon in place date of 2018, so in theory, NO GAS STATION should still be using them. There are many grants, most at the state level, for replacing single walled tanks and upgrading the associated dispenser network. In addition to using double wall tanks, secondary containment is also required, as is regular tank integrity testing - none of these things used to be in place. Double walled tanks do still leak, however, testing tells us very early if there’s a problem, and secondary containment is there specifically to prevent leaks from leaving the tank area. It also helps that if tanks fail integrity tests, the license to distribute is pulled until the problem is fixed. Most tank owner proactively change them now as a cost-of-doing-business, and most leaks are discovered and cleaned up during those upgrade intervals. New releases (from double wall tanks, which started being put in place in the 90s and are the ones coming up on their warranties mentioned in the article) are few and far between these days. I’ve had three “new” release cases assigned to me in the last ten years. Of those, one was actually from a previous single-wall release discovered while renovating the station, another wasn’t actually a tank at all, but an illegal sump we treated as one, and the third has been assessed, remediated, and is already closed. In that case, the double-wall tanks and secondary containment and early detection all worked to minimize the damage, and very little petroleum left the tank area.

As for the contaminants - the ones you hear about and should worry about are Benzene and MTBE - they are both carcinogens, and they are both additives in just about all brands of gasoline (benzene always, MTBE 90% of the time). If either of these have impacted drinking water - that’s bad, but it’s not all doom and gloom. Unlike some other very nasty contaminants we need to worry about that are VERY widespread (PCE, TCE, PFAS for example), benzene and MTBE break down on their own over time. That’s not to say we shouldn’t clean them up, or that they aren’t to be worried about BY ANY MEANS, but the silver lining is that with isolating and monitoring they WILL break down into non-threatening biproducts and eventually disperse completely. It also makes them easier to remediate, because we have more options. The reason the stations have vents to atmosphere is because oxygen exposure is what rips benzene apart into non-hazardous biproducts, and the vents prevent benzene from building up under the concrete pads and becoming a vapor intrusion risk. Not saying we should be pumping benzene into the atmosphere, but the reality is the fuel is going to be burned and end up in the atmosphere regardless and that’s an entirely separate (global) issue. In this case, bypassing the ability to expose people to concentrated carcinogenic fumes is a good thing and venting them to the environment where they immediately start to break down is sound. MTBE is less of a concern in this case because MTBE prefers to remain in the liquid phase, and does not readily volatilize. It’s daughter product (tertiary butyl alcohol, or TBA - also nasty and is a suspected carcinogen) is even more stubborn. So they’re harder to get out of water, but on the plus side, they are not inhalation or vapor intrusion threats like benzene.

If anyone read all that, you’re a trooper! I hope it helped and I’m happy to answer any questions if I can!

This was such an awesome read!! Thank you for your insight into this!

Glad you liked it! Hopefully it helps some people.

thank you for the additional input, as someone actually in the field!